The European list of critical materials includes as many as 34 raw materials. What is your personal top three?

Chahim: “Oh no, I’m not starting that discussion. Nor am I going to explicitly tell you which raw materials are critical. We ask experts which raw materials are strategic. That can mean scarce because it comes from a limited number of countries. In that case, the political stability of such a country is very important. Beyond that, of course, what counts is the extent to which you depend on certain raw materials for the economy.”

Sprecher: “I choose the duo of neodymium and dysprosium, on which I obtained my PhD. You will find them in everything from Joint Strike Fighters to wind turbines. At number two is copper. According to the European analyses, it isn’t ‘critical’, but amusingly was added later on because of its obvious importance for everything electric. Third is lithium because the price keeps falling while all predictions say there will be huge shortages. I find that contrast fascinating.”

Europe has hardly any mines and very few reprocessing plants. The energy transition is increasing demand. So how will we resolve that?

Chahim: “I think Europe should first map out which raw materials we have within Europe and which we don’t. In many past mining operations, critical raw materials may have come to the surface as by-products and may therefore still be in the old mining waste. We also want to impose many more obligations to reuse raw materials. And thirdly, we also want to set up strategic projects.”

Dr Mohammed Chahim (Fes, Morocco, 1985)

© Portrait: European Parliament | Montage: Ontwerpwerk

Who is Mohammed Chahim

Dr Mohammed Chahim (Fes, Morocco, 1985) joined the Dutch Labour Party PvdA in 2002 and was elected to the Helmond municipal council in 2006. He holds a degree in econometrics and operations research from Tilburg University and obtained his PhD there in 2013. He then joined TNO as a researcher specialising in sustainability, energy and circularity. In 2019, he made a switch to the European Parliament and became vice-president of the Social Democrats in 2021. “What I do in Brussels is no different from my work in Helmond,” Chahim explains: “I fight unfair systems and promote solidarity. My main priorities are climate policy and the energy transition. We need to get Europe carbon neutral by 2050.”

Who is Benjamin Sprecher

Dr Benjamin Sprecher (The Hague, 1985) is an associate professor and researcher at the Faculty of Industrial Design Engineering. He is one of the authors of the report Critical Materials, Green Energy and Geopolitics: A Complex Mix. Sprecher studied industrial ecology at TU Delft and Leiden University (2003-2010). After obtaining his PhD in critical resources, he moved to Yale for a post-doc. In 2017, he joined Leiden University as an associate professor, before switching to Delft in 2021. According to Sprecher, product designers bear a great responsibility: “Use materials and technologies with fewer critical metals; Extend product lifespans by enabling repair and reuse; And commit to recovering raw materials at the end of the product lifecycle.”

Dr Benjamin Sprecher (The Hague, 1985)

© Portrait: Guus Schoonewille | Montage: Ontwerpwerk

What do you mean by strategic projects?

Chahim: “That we identify what raw materials we need and then establish partnerships with countries to ensure we have access to some of their raw material. For example, we can set up a reprocessing plant together. This is how you create a win-win situation between a third country and Europe. We gain access to their mines and set up a battery factory locally in return.”

What is your solution, Benjamin?

Sprecher: “I think that, above all, Europe needs to be smart. René Klein always used to say: ‘those rare earth metals are not irreplaceable. You can do without them, it’s just a matter of lazy engineering.’ It is just a bit easier to make something with neodymium than without. So I think it’s smart to pay more attention to your product design and thus become less dependent on those raw materials.”

‘We should not be constrained by today’s economic conditions’

Last year, a Swedish mining company announced that rare earth metals were allegedly found in Kiruna. Benjamin then said Europe would remain dependent on China anyway because extraction is too expensive. What’s your view on this?

Chahim: “We should not be constrained by today’s economic conditions. There are several reasons why we want to reduce our dependence on certain countries. Firstly, due to strategic autonomy. Secondly, the moment something happens in the supply chains, as happened during Covid, for example, you could be in trouble. So you also have to have your own production and refining to make the economy more independent. A third argument is that if we decide to mine and process raw materials in Europe, we also develop the expertise, technology and efficiency to do so. In the past, we got rid of the refining of lithium and a number of other critical raw materials, for example, because it was a polluting sector. If we were to bring back extraction and purification now, we would try to do that in the cleanest way possible by boosting that technology. I am convinced of that.”

As an economist, you know that industry looks for the cheapest raw materials. How do you ensure that responsible raw materials from Europe have a chance even though they are more expensive than imports?

Chahim: “That is a good question, and something that we have thought about too. ‘Carbon contract for difference’ projects have emerged from this. These are designed to ensure that technology development is not slowed down by a lack of demand. For example, the hydrogen bank. This will match hydrogen supply and demand for 10 years. The hydrogen bank bridges the difference between the highest offer and the lowest price. We pay for this with part of the revenues from CO2 emissions trading. I think we should also set up something like this for critical resources. Then you are creating supply and demand simultaneously.”

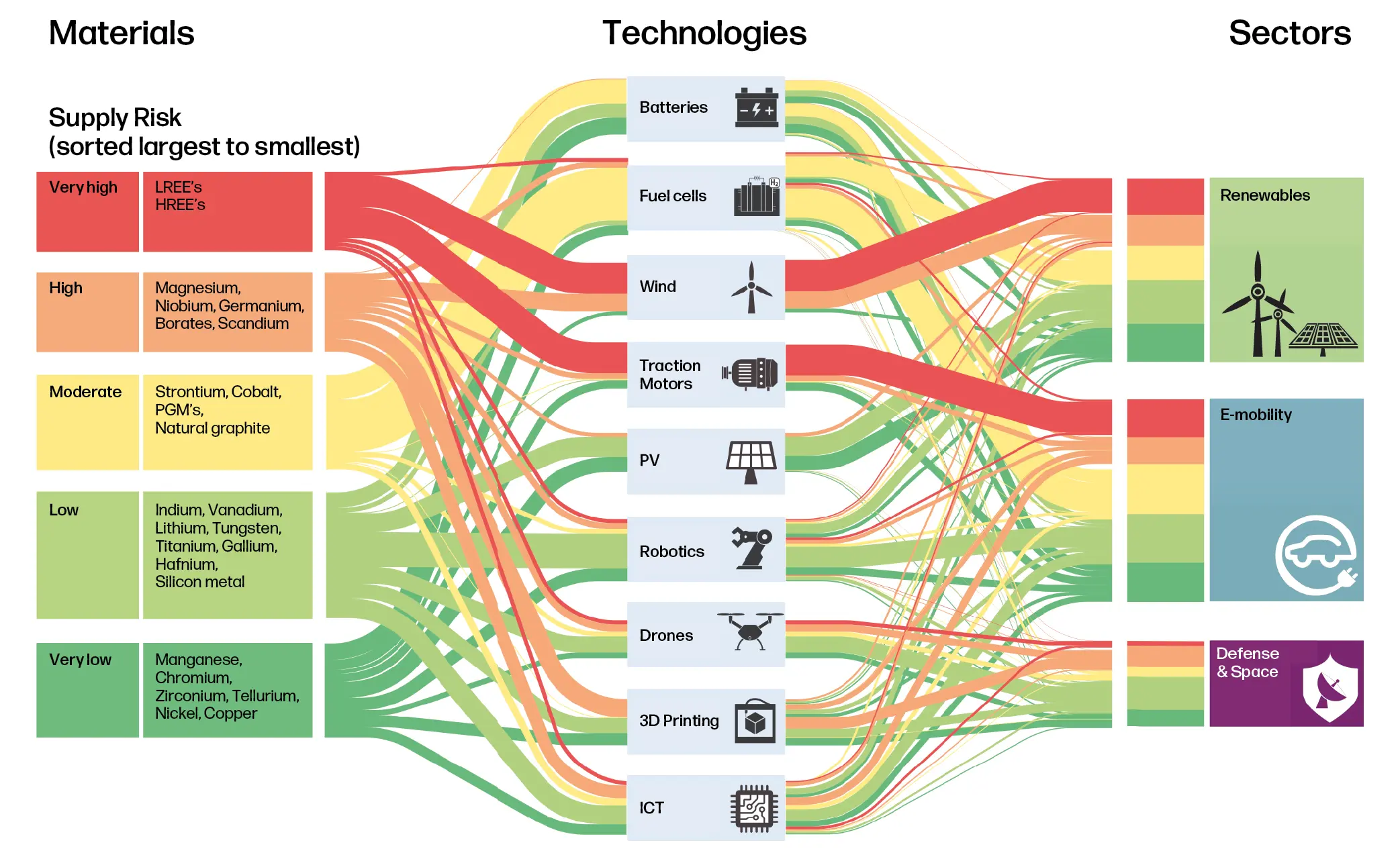

To estimate future demand and competition, raw materials, technologies and sectors must be considered together, as different technologies and sectors compete for the same materials. (Source: EU report ‘Supply chain analysis and material demand forecast in strategic technologies and sectors in the EU – A foresight study’.)

Care to weigh in, Benjamin?

Sprecher: “I think that Europe does good work. To be honest, it couldn’t be doing much more. Where it gets stuck is national legislation. I’m talking about the quality here.”

Could you give an example?

Sprecher: “I think it’s a bit stupid to burn down individual projects. Let me use another example, from the construction industry. There’s the Environmental Building Performance, EBP, which, on paper, looks good, but it is really poorly implemented because it is outsourced to a party that simply does not have the technical capacity. And then it goes wrong.”

Chahim: “There is a tension in Europe, I think, between what you leave to the market and what you can do to steer the market in a certain direction.

‘That entire raw material story is simply not really about free markets’

If you look at strategic autonomy and energy transition, we are very dependent on other countries to achieve those goals. We have some great plans, but implementation often reveals problems and inequalities between member states. But the Critical Raw Materials Act is a law. They are targets imposed on all member states, and that creates tension, of course.”

Sprecher: “That’s the crux of the problem, I believe. That entire raw material story is simply not really about free markets. China is not a free market. America works through the Pentagon. And we pretend it is a free market. Then we intervene very slightly. That’s not going to work. I think we will muddle along for another 10 years and still fail to meet the target. Unless member states go a step further and adopt a kind of industrial policy. Not intervening in the market, just taking over and doing it yourself. It is something that Europe is completely out of practise with. I wonder what you think about that.”

Chahim: “I am quite outspoken in that. I wrote earlier in an opinion piece that the government should become much more of a co-investor in new technologies. Because with that, you are doing two things. Firstly: you are showing that you believe in it because you are taking a risk. And secondly: you are also steering the market in a certain direction.”

Green Deal and critical raw materials

A fair, healthy and climate-neutral economy by 2050. To get there, the European Green Deal leans heavily on a large number of critical materials. How does Brussels plan to secure those materials? The Critical Raw Material Act (CRM Act) is an important part of the European Green Deal that revolves around securing critical raw materials. The EU has defined critical materials as commodities that are of crucial importance to the economy and have a high supply risk, for example due to supplier scarcity. Since the invasion of Ukraine and the shift in the geopolitical landscape, Europe has become more aware of the vulnerable position that its dependence on such materials puts it in. There are 34 critical raw materials on the 2023 list, some of which play a key role in the energy transition. Lithium, cobalt and nickel, for example, are used to produce batteries, while gallium is needed for PV panels and boron for wind turbine blades. On top of that, we will need copper and aluminium (bauxite) to expand and reinforce electrical grids. The strategy advocated by the CRM Act, besides establishing and strengthening European supplies, is to expand networks with other suppliers through mutually beneficial partnerships. By 2030, the EU aims to extract 10% of critical raw materials in Europe itself, as well as relocating 40% of processing and 15% of recycling to Europe.

No more than 65% of any material may then still be sourced from a single non-European country. While the trend is clear, the road to greater material independence is long. Electronics recycling, for example, is struggling to take off, with the Netherlands collecting 11.75 kg of electric and electronic waste per capita in 2021, just over the European average of 11 kg. While this may sound promising, it accounts for only 45% of all new purchases in the previous years, far below the targeted 65%. Opening new mines is costly and puts significant demands on locals , argues Jojo Nem Sing (Erasmus University Rotterdam) in the LDE report ‘Critical Materials, Green Energy and Geo politics: ‘A complex mix’ (2022). And yet, strategic interests dictate that Europe will have to build its own mining industry, even if it means incurring major losses. Benjamin Sprecher (TU Delft) adds that the laws of the free market do not apply to critical materials. “China has come to dominate the markets for many critical materials because of active government support of certain sectors,” he writes in the same report. “Europe should follow suit, as leaving resource politics to the whims of the free market has proven to be a bad idea.”

Sprecher: “May I broach another subject? Europe, just like TU Delft, is obsessed with innovation. We rarely talk about design. There are companies lobbying for more innovation and more investments, but never once is anyone asking for less, or for things to be done differently.”

Chahim: “In the Critical Raw Materials Act, we have set increasing targets for recycling so that it becomes almost impossible to make products that are not reusable, at least in parts. I agree that it is still insufficient. Companies only want to make changes very gradually, such as replacing some of the raw materials with recycling.”

Sprecher: “Yet that is the only way out of this problem. Industry needs to adjust its designs to use fewer raw materials, otherwise we will be having the exact same discussion in 20 years’ time. So what can we do about it?”

Chahim: “The problem is, Benjamin: I am not a dictator and neither are you, so we must do things collectively. I hope that companies will start to realise what a future in Europe demands of them, that it can also make them trendsetters.”

Sprecher: “That’s what I mean. Those laws about design are so incredibly lax.”

Chahim: “I disagree. The Ecodesign Act (’Ecodesign for Sustainable Products Regulation’, ed.) sets requirements for products in terms of durability, repairability and circularity. Everyone thought that was meddlesome, but that law is proving hugely successful. Only longevity was dropped from consideration.”

Sprecher: “But that very thing makes a lot of difference. If your laptop were to last twice as long, you would need half as many raw materials. I have seen how incredibly small the adjustments are between a laptop lasting three years or 10 years. It is sometimes a matter of 10-cent production costs. Everything is about recycling now, but recycling is no quick fix, it’s a last resort. I wonder how we can pay more attention to that?”

Chahim: “How about this. We continue this chat some other time, either online or in Delft. Then we will go over the law and I want to hear what you, an expert, would like to add, or formulate differently. And then we can look at what difference I can make. I would find that interesting.”

Sodium battery

Imagine if we had a sodium-carbon battery that could be fully charge in 9 minutes, held a stable charge and was made of readily available sustainable materials. Prof. Marnix Wagemakers and his team (Faculty of Applied Sciences) are developing such a battery as a cheaper alternative to lithium-ion batteries. Sodium has long been mooted as a potential replacement for lithium, but researchers have been hamstrung by limited storage capacity and lifetime so far. The sodium battery introduces a new crystalline structure of carbon with wedge-shaped pores that combines high storage capacity with highly mobile Na+ ions that can move in and out easily. The result: a fast-charging, high-capacity battery that has a much longer life span than previous sodium-ion batteries to boot.