In five years, 70% of Dutch energy must come from renewable sources. This means using batteries instead of petrol and heating your home without gas. But is our electricity grid ready for that?

Ramirez-Elizondo “Not yet. We not only use more and more electricity, we also generate increasingly more with things such as solar panels, for example. The electricity grid is facing more strain from all sides and there’s the risk of grid congestion when it gets too busy. And, unlike fossil fuel sources, energy generated from solar power and wind is difficult to control. You can switch a gas power station on and off. The same cannot be said about the sun. Our power grid is just not prepared for that.”

Oskam “The electricity sector wants to be 100% carbon-free by 2035, and we’re on track to achieve that. The Netherlands is still seeing exponential growth in solar energy. And the potential of wind power is huge in our country. So I’m hopeful.”

Ramirez-Elizondo “Saying we are not going to achieve it is not an option. You have to keep that goal in mind because only then will you feel enough urgency to devise creative solutions. An improved electricity grid is a prerequisite for the energy transition. The faster it’s ready, the faster the transition.”

‘We all come home at 5 pm, plug in our car and turn on the lights, the heat pump and the oven’

What needs to be done to achieve the stated goals?

Oskam “We need to roughly double the electricity grid to meet the 2035 target. This requires opening one in three streets. That’s really the biggest challenge. Do we have enough space for all this new infrastructure? And who will lay those cables? If we get those things in order, we can achieve our goal.”

Ramirez-Elizondo “Smart technology enables us to get more out of the grid. At TU Delft, we are working on energy hubs that ensure the more efficient use of available energy. For example, using energy when it is available and supplying it when there is a surplus.”

Energy hub

An energy hub is a decentralised energy system that aligns local energy supply and demand. Instead of returning surplus power directly back to the overloaded central grid, an energy hub stores it locally or efficiently distributes it. This helps reduce peak loads on the central grid and makes energy supply more flexible, reliable and efficient.

For example, the hub can temporarily switch to stored heat instead of using a heat pump to compensate for times when there is less power available. The system uses smart software and control algorithms to make continuous choices, resulting in lower costs, reduced CO2 emissions and a more sustainable energy system.

Focus on flexibility is the only way to keep the power grid affordable, says Hans-Peter Oskam.

© @canada_by_alexis

Laura, you said earlier that, unlike fossil fuel energy, renewable energy is difficult to control. You can’t just turn on the sun on a cloudy day or crank up the wind when needed. What implications does this have for the electricity grid?

Ramirez-Elizondo “The electricity grid should always be in balance, i.e. the electricity supply must equal the demand. If that is not the case, the frequency changes. An increased imbalance could cause lights to start flickering, for example. And if it is not restored quickly enough, you run the risk of blackouts. In the past, it was easier to maintain that balance because we only used controllable sources that you can easily switch on and off. Renewable sources come with more uncertainty; you’re never completely sure when the sun will shine. An increasing amount is also being generated locally by, for example, solar panels on homes. People are delivering back to the grid from all kinds of locations, which makes it even more complex.”

What does this complexity mean for the future energy system?

Oskam “The increased fluctuation of both supply and consumption causes much higher spikes. We need a wider bandwidth to accommodate that. That’s also our biggest challenge, rather than electricity demand in general. The new system is substantially different from what it was. But complexity is not bad or scary.”

Ramirez-Elizondo “The complexity and diversity enable us to come up with solutions such as dynamic consumption, storage and other energy sources. You can devise all kinds of things to maintain the system’s balance.”

Oskam “It would be good to start considering energy more as a resource that we use when it is available. A cold, windless February day may not be the best time to run a factory at full capacity. The only way to ensure that it remains affordable is to focus on flexibility. It’s also fairer: every country can capture solar power and wind, leading to less dependency on countries with plentiful oil or gas resources.”

‘You wouldn’t build a five-lane motorway to Zandvoort for those three days a year when it is incredibly busy’

What does this mean for people at home? It’s precisely when the sun is not shining that we want to turn on the heat, cook a meal and watch television.

Oskam “The Dutch are real creatures of habit. Even if we’re all living sustainably soon, we will still all come home at 5 pm, plug in our car and turn on the lights, the heat pump, the oven or the induction hob. So we would see a huge spike between 5 and 9 pm, especially in winter. Focussing on that would require an infinitely large electricity grid, which is neither necessary nor wise. You wouldn’t build a five-lane motorway to Zandvoort for those three days a year when it is incredibly busy. So we are looking at how we can accommodate that spike in other ways.”

Ramirez-Elizondo “That‘s precisely what our department does. We think of ways in which that flexibility is feasible. For example, I’m working on the ‘charging station of the future’, to charge electric cars. What mechanisms can we build in to ensure that the car charges when there is an available surplus of energy and does not charge when that’s not the case? And how do you make sure it feeds it back (or not) at the right time? Another project concerns hybrid storage at the district level. It’s about all these different levels, from very local in your own home to much larger.”

Oskam “Price incentives also help encourage flexibility. That is why, for example, it’s good that the net metering scheme is being abolished. This motivates people to use energy generated from their solar panels for the car or washing machine on sunny days instead of feeding it back to the grid. We also see a lot of creative entrepreneurs focussing on flexibility. The Watthub in Geldermalsen is a great example of this. Located next to a solar farm and three wind turbines, this is a huge charging plaza for heavy transport and construction vehicles. They are exploring how to combine that smartly on one cable, which also makes it more affordable. The more we can do with the available capacity on the grid, the less we need to invest.”

Should we look beyond electricity?

Ramirez-Elizondo “In the future, we will have a system that includes electricity and heat, for example. Storage is also important because solar and wind are not always available. This can be done in batteries but possibly also with hydrogen. We’re looking into how houses, businesses and charging stations can ‘talk’ to each other and recognise the smartest way to heat a house at a particular moment, for example. Is it solar energy from your own solar panels, heat from the heating grid or tapping into the stored supply? Technical developments are moving rapidly but we have to play it smart to ensure we can apply them.”

Oskam “The intention was for one-third of homes to be heated with electric heat pumps – this is now going to two-thirds. That’s double the required capacity! The share of heat networks is lagging behind and we really need to put more effort into that. The same applies to insulation because so much energy is currently being used on heating the outside. That’s a waste of energy and grid capacity.”

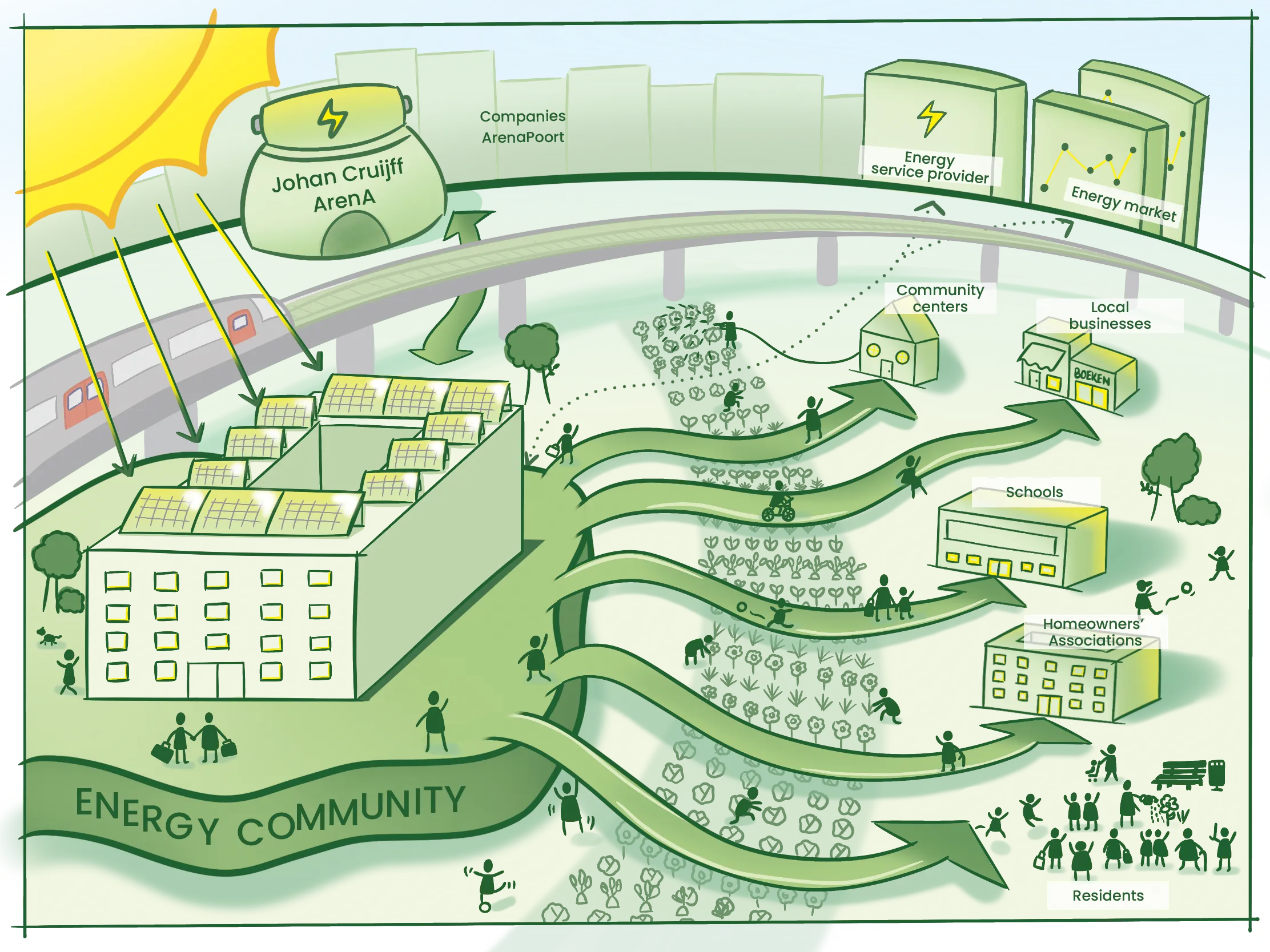

Explaining to residents how the energy cooperative could work.

© Photo Abhigyan Singh

From energy poverty to energy hub

The Johan Cruijff Arena generates energy with its thousands of solar panels. But should there be a few months without any events, the excess power is fed back into the already overloaded central electricity grid. At the same time, many households in the adjacent Venserpolder neighbourhood struggle to pay their energy bills. Could stored energy help reduce local energy poverty? The Local Inclusive Future Energy (LIFE) project, a collaboration of 12 partners that includes AMS Institute and the City of Amsterdam, is working on an energy hub in the ArenAPoort area. This should ensure that energy surpluses are utilised locally instead of going to waste.

Energy cooperative

Abhigyan Singh, assistant professor of design anthropology for social change, focuses on the social aspect of the project. “The energy transition is about technology, infrastructure and businesses,” he says. “If we want everyone to benefit, we must also consider the people themselves.” He is working with PhD student Gijs van Leeuwen and CoForce, a project partner involving residents, to investigate how residents can organise themselves into an energy cooperative. Such a cooperative can provide access to cheaper, locally generated energy but it also requires a more conscious use of electricity. “Many people in the neighbourhood already have a lot on their plates,” Singh says. “Which means that they do not necessarily give much thought to the energy transition.” To build trust and get insight into residents’ perceptions, the researchers spent time in the neighbourhood and spoke to people in community centres, at markets and at local events to hear their concerns. “You can’t expect people to feel engaged if you don’t know their daily reality,” Singh says.

Lego models

The team uses Lego models to make it easier to understand how the electricity grid works. They have meetings during which they demonstrate how energy flows through the neighbourhood and how the energy cooperative can help make better use of locally generated power. This helps residents better understand their own energy consumption and how they can contribute to solutions. “Not everyone has to be actively involved,” Singh stresses. “Someone providing their opinion via an occasional text also counts as participation. But the more people participate, the stronger the initiative.” He warns: “The energy transition will only be successful if we ensure that diverse social actors – including vulnerable groups – can help shape and share in its benefits. At the moment, it mainly benefits large companies because they have the resources and knowledge to get involved. If we do nothing, an energy elite will emerge, while others will be left to deal with high costs.” LIFE wants to use the energy hub and energy cooperative in the ArenAPoort area to show that the energy transition can also be a social solution.

Sun and wind are not always available, which is why storage is important, stresses Laura Ramirez-Elizondo.

© Lorado

How can we keep it affordable?

Oskam “As grid operators, we’ve calculated that we need to invest 219 billion. This would be unaffordable if we passed it all on to the customer. So it now becomes a political question: how are we as a society going to bear that cost? I think it is especially important to stress that keeping the current system is the most unaffordable option. Switching will of course cost money, but it will always be less expensive than continuing on the current path.”

Ramirez-Elizondo “Fossil fuels seem cheaper in the short term but are more expensive in the long term. They become depleted and reserves run out. Even if we should discover more oil now, we would have to ask whether the benefit outweighs the environmental damage.”

It can sometimes take months before a new residential area is connected to the electricity grid. Around 10,000 companies are currently on the waiting list for a new connection. How can this be sorted faster?

Oskam “Network operators are utilities meant for the public interest. It’s awful that we cannot serve everyone. We need to expand as soon as possible and consider all these smart options. At the same time, procedures need to be faster. All the spatial claims we’ll need in the coming 15 years should be registered as soon as possible. We need to find a solution for the nitrogen issue, which is now causing far too many delays. And licensing needs to happen faster.”

Ramirez-Elizondo “The Netherlands is a country of consultation before action. It’s fantastic that everything is so well thought out. There are countries where there is no serious consultation on this issue, which is even worse. But with or without consultation, sooner or later we have to act. The energy transition is not a national issue, it is an urgent global challenge.”