Text Kim Bakker

A future-proof city doesn’t depend on fossil fuels. A collective, sustainable heat network can offer a solution. What needs to happen first?

It is hanging on increasingly more external walls of Dutch homes: the external unit of the heat pump. It seems almost inevitable for anyone deciding to come off gas. Yet in the Oude Gracht district of Eindhoven, they are adopting a different approach, explains local resident Yolanda Knops, who graduated with a PhD as an applied physicist from TU Delft and now works for ASML. For the past two years, she has been working with five other neighbourhood residents to investigate how the neighbourhood can switch to natural-gas-free heat. In her area, the residents prefer not to see a heat pump in every dwelling, but a communal heat network, to provide the entire area with natural-gas-free heat. “By investigating whether a collective sustainable heat network is suitable for our area, we want to prevent people from having to invent the wheel themselves and having to switch to a heat pump individually.”

Resilient city

The fact that not everyone has to find out everything themselves is just one of the many advantages of heat networks in the energy transition, explains Arnoud van der Zee, Energy Transition programme manager at The Green Village. In that testing ground on the TU Delft campus, his focus lied on innovations in heat networks, among other things. According to the programme manager, heat networks are perfect for making a city future-proof – not just because they can be used to heat homes without burning fossil fuels, but also because the heat is generated locally, rather than far away. “The energy crisis shows that dependence on foreign sources is a fragile business. It makes us more resilient if we are able to manage the source ourselves.” Yet the government now seems to focus on individual sustainability, with funding for heat pumps and solar panels. Which is a good thing, says Van der Zee. But there is a reverse side to this. “Even with grants, individual sustainability is something for the lucky few. If you feel even a little bit of social responsibility, you should take everyone along with you.” A heat network whose installation is paid for by a municipal energy company, for example, and for which residents only pay when they use it, does not require major one-off investments by residents.

An underground pipeline with residual heat from the Port of Rotterdam is to heat homes and businesses in South Holland (Vlaardingen, Delft, Rijswijk and The Hague).

© ANP/Laurens van Putten

HEAT-COLD STORAGE

The very-low-temperature heat network is often combined with an open ground energy system, also known as heat-cold storage (HCS). That system consists of two underground sources: a hot one and a cold one. In the winter, a heat pump draws heat out of the heat source, which is then used to heat a home. The cooled groundwater is pumped back into the cold source, so it can be used in the summers to keep the house cool. If the need for heat and cold is in balance, an alternative source is not theoretically required. Heat-cold storage is already common for offices and other utility buildings. As far as homes are concerned, there are a few examples such as the MijnWater project in Heerlen and the new heat network in the Pijnacker districts of Keijzershof and Tuindershof.

‘Even with grants, individual sustainability is something for the lucky few’

Complexities

But if you want to install a heat network, you will find yourself in a web of complexities. Thijs de Booij, TU industrial design engineering alumnus and director of consultancy firm De WarmteTransitie-Makers, knows all about this. His company specialises in supervising the switch to natural-gas-free heat. There are two choices: a collective heat network or individual sustainability. De WarmteTransitie-Makers incorporates ‘everything’ in its advice, often to municipalities, says De Booij. “If a heat network appears to be the best solution, we investigate how to tackle that. That means lots of talking to residents, drafting plans, setting up a heat company if necessary or organising tenders and the technical execution.”

Different choices

In order to be able to better answer technical questions, De WarmteTransitie-Makers took over heat network developer Greenvis in 2021. There are different choices of heat networks, explains Greenvis director Frits Verheij. In the case of conventional high-temperature heat networks, that is often residual heat, for example from power stations where natural gas is converted into electricity. Although that is more sustainable than a personal central heating boiler, natural gas remains the initial source. New heat networks often make use of residual heat, but that increasingly comes from industrial companies or data centres, for example. The Municipality of The Hague, for example, is investigating whether residual heat from the Port of Rotterdam could heat the district of Hofstad, and the Groningen districts of Zernike, Paddepoel and Selwerd have recently been heated with residual heat from QTS Data Centers.

Several buildings in Heerlen get their heat or coolness from the Mijnwater Network, the world’s first mine water power plant. Underneath the city is a huge system of mine tunnels that have been flooded with groundwater warmed by the earth since the mines closed.

© ANP/Branko de Lang

Medium temperature

Residual heat from those sources is suitable for a medium temperature heat network of a maximum of 70 degrees. The national research programme WarmingUP, under the leadership of the Netherlands Organisation for Applied Scientific Research (TNO) and Deltares, which was conducted in March, revealed that ninety-five percent of Dutch homes are equipped for this. However, such a source needs to be local, because otherwise too much heat would get lost en route, explains Verheij, who led the programme before starting at Greenvis. Another option is a low-temperature heat network of a maximum of 55 degrees, for which sources such as geothermics/shallow geothermics, aquathermia and riothermia (from waste water) are suitable. This involves extracting heat from the ground or the water. A small heat pump is necessary, however, to make the water suitable for showering and drinking: the water must be heated at a higher temperature so as not to give legionella bacteria a chance. WarmingUP has revealed that 60 percent of Dutch homes are suitable for a low-temperature heat network such as this. What was striking was that the year of construction and type of home didn’t appear to be decisive factors, explains Ivo Pothof. He is a guest researcher in sustainable heat/cold networks at TU Delft and was involved in WarmingUp via his work as a researcher at Deltares.

Overdimensioning

Much more important than year of construction or house type is what Pothof refers to as ‘overdimensioning’. “A heating system often has much more power than the house requires, because the home has been better insulated since it was built. In that case, the temperature can be reduced.” So, according to him, there is no need to wait for a heat network or your own heat pump to become more sustainable. “Many people keep the central heating boiler at a standard heat of 75 degrees. There is a big possibility that this figure can be reduced to 60, or even lower to perhaps 50.” In Eindhoven, the question is whether the houses are being heated sufficiently with a low-temperature heat network, with residual heat from the sewage water purifier as the intended source. Knops explains: “We may need a booster module to raise the temperature to 70 degrees. That could be a type of large heat pump, or we can make use of solar collectors.” But before we reach that stage, the core team will check whether the homes are perhaps suitable (or could be made suitable) for a low-temperature network.

‘Whoever installs a heat network, enters a web of complexities’

© ANP/Kees van de Veen

In Groningen’s Paddepoel district, a heat network is being constructed using residual heat from data centres. This could eventually heat more than 10 thousand households, buildings and knowledge institutions in Groningen’s northern districts. The pipes for this heat network are stored in the depot at Zernike.

NEW HEAT NETWORKS MASTER’S TRACK

Since September, TU Delft has been the first university in the Netherlands to offer the heating-and-cooling track within the Master’s in Sustainable Energy Technology. To strengthen the field, new assistant professor Bram van der Heijde was appointed. The Master’s track was set up because knowledge at TU Delft about heat networks has been limited so far, explains Ivo Pothof, who is involved in the degree programme in the background. “The Master’s programme mainly focused on electrification, whereas the heat supply is also an important part.” Pothof has personally been working at TU Delft one day per week on an interdisciplinary heat network programme since 2018.

Very-low-temperature network

To be really prepared for the future, we would do well to answer the demand for cooling too, says researcher Pothof. “We know for certain that it will get warmer. You don’t want people to purchase air conditioning units en masse, because those guzzle electricity and cause the outside air to heat up even more.” So, when it comes to sustainability, he prefers that greater attention be paid to the increasing demand for cooling. A very low-temperature heat-cold network of a maximum of 20 degrees in the ‘hot’ pipe and around 10 degrees in the cold pipe can heat and cool homes very efficiently. Heat pumps in homes are therefore required for heating and tap water.

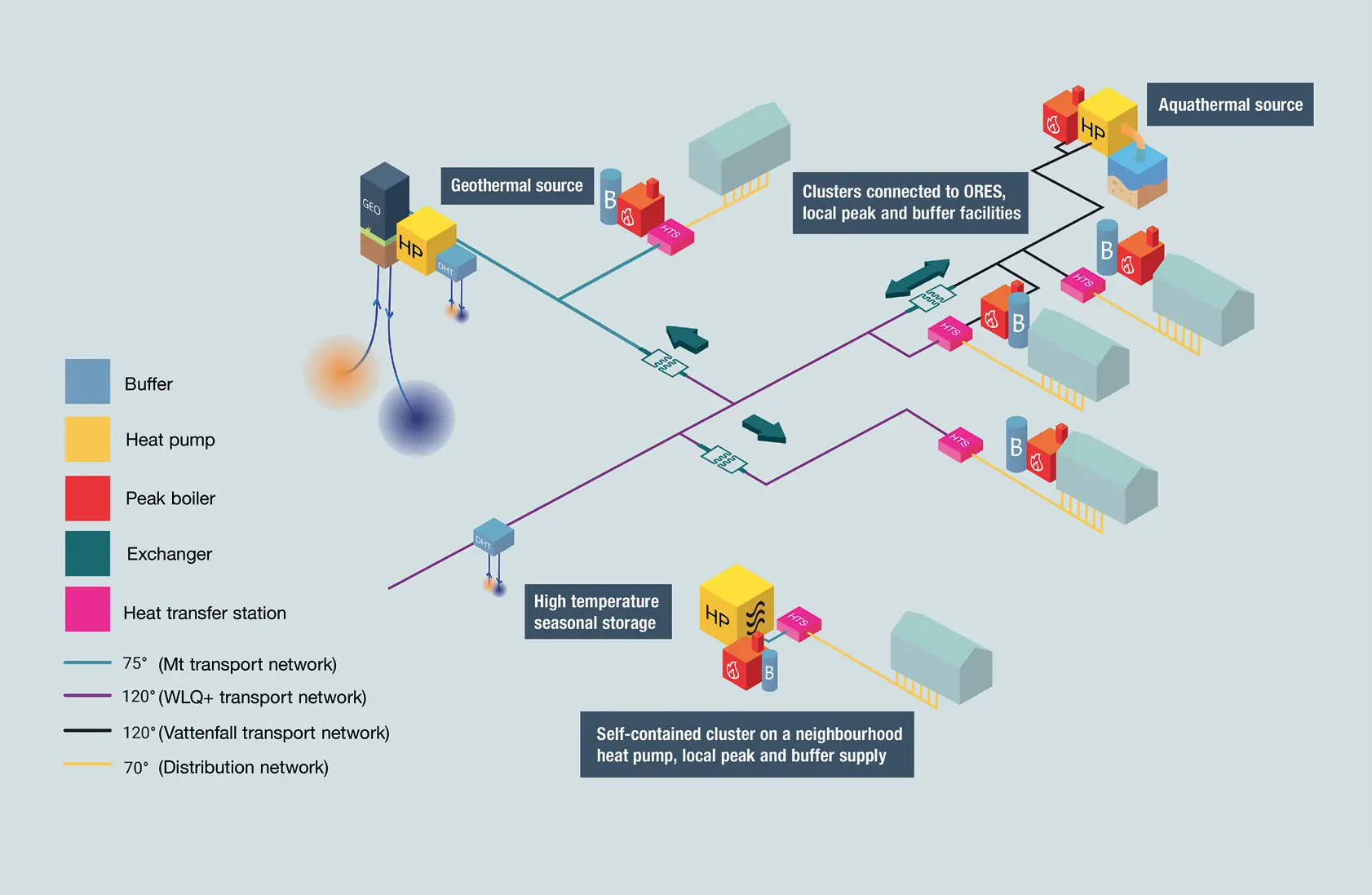

Schematic design of a regional heat grid (ORES).

The local area

If it emerges that a heat network, of whatever variety, is technically feasible, this does not yet eliminate all obstacles. At present, many heat network projects are running aground due to a lack of government regulation, says Van der Zee (The Green Village). “Municipalities are only switching to a heat network if a certain percentage of households participate. But those households don’t just simply fall into your lap.” He encourages a bottom-up approach, like they have in Eindhoven. “Waiting until plans are made from the top takes too long. Individual sustainability is a lot of hassle, demands a lot of people and with large installations takes up a lot of space in and around the house. A local heat network enables us to maintain speed in the energy transition.” But not everyone is enthusiastic about it. For example, because they fear hassle in the home, whether it is a rental property or an owner-occupied home. Verheij explains: “I know a man who is 80 years old who says my central heating boiler will last another 10 years, by which time I won’t be living here anymore, what sense does it make for me? That is quite understandable.”

Slow process

So, the question ‘how do you enthuse your residents?’ is an important one. It helps if a heat network has been organised locally by the municipality, for example, or an energy cooperative, says De Booij (De WarmteTransitieMakers). “That evokes confidence.” In Eindhoven, the municipality stipulates that it needs to receive at least 70 percent public support, explains Knops. From her perspective, commitment from the area has turned out much better than expected. “On the first residents’ evening, people simply kept wandering in. Almost 30 percent of the neighbourhood turned up.” It is now up to Knops’ team to maintain that enthusiasm until all investigations are out of the way, participation is at the required level, funding is in place and all signals from the municipality have been given the green light. She hopes that the neighbourhood is gas-free by 2030.

© ANP/Laurens van Putten

Construction of Warmtelinq heat network under the Prinses Beatrixlaan in Rijswijk.

Acceleration

According to Pothof, that’s not fast enough. “The individual sustainability route simply continues. Everyone who can afford it is installing heat pumps and air conditioning units. That places a much greater strain on the electricity network than a collective approach. So, in the winter, we are running the risk of the power grid failing.” In addition, the business case for heat networks will be more problematic as more people take individual measures, thinks Pothof. Heat networks can only continue if they have great enough support, and that is becoming increasingly smaller as more people opt for individual solutions and therefore no longer require a heat network. The government therefore needs to act much more quickly, says Pothof. “Ministries don’t realise enough that because of their slow decision-making, support for heat networks is becoming eroded, resulting in the energy transition only becoming more expensive. People don’t realise the urgency to a sufficient extent.”