The eternal life

of wind turbine blades

Text Jos Wassink

The first generation of wind turbines is dropping their blades. The durable polyester is a harbinger of the deluge of discarded material that awaits us. Is there anything we can do with it? There are numerous original uses.

Polyester plague

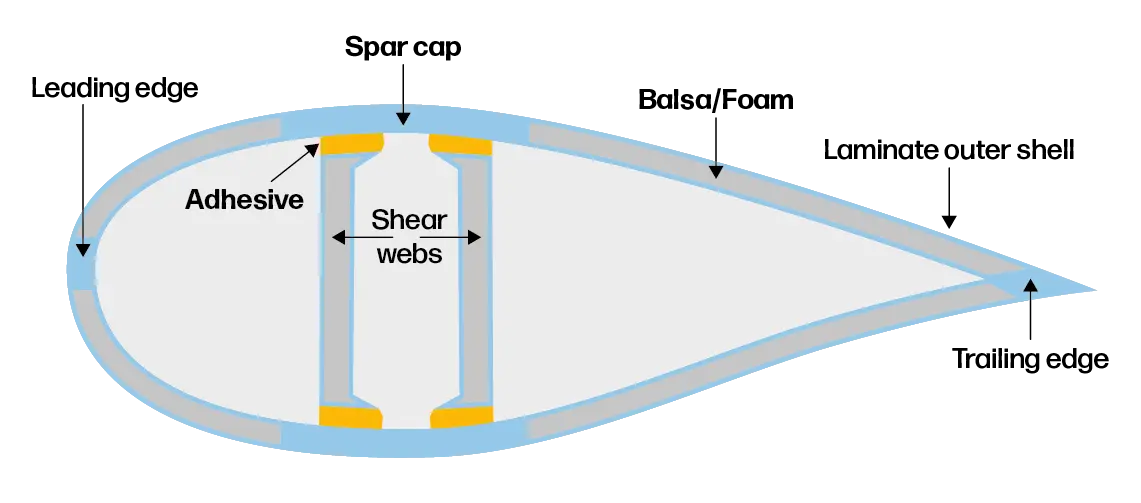

Still, the time comes that every wind turbine is decommissioned. The concrete foundation and the steel mast can be reused, but this is not easy for the blades. The composite material consists of glass or carbon fibre soaked in epoxy, polyester or vinyl ester synthetic resin. It is rock hard, rigid and weatherproof. Put it in a landfill and it will remain there for another 1,000 years. Wind turbine blade dumping will be banned in Europe by 2025, but in the Unites States of America it can still be done. Drive them to a desert, dump them and cover the stash with sand. Problem solved.

Or is it? Worldwide, some 14,000 blades were discarded through to last year after an average useful life of 20 to 25 years. For the Accelerating Blade Turbine Circularity (2020) report, WindEurope, the European wind energy industry association, and its partners calculated that this amounts to 40,000 to 60,000 tonnes of composite waste. This is the waste from the early years of wind energy when wind turbines were sparse. For the Netherlands, the polyester problem will become topical in around 2027 when the Amalia offshore wind farm will be decommissioned and 180 blades will be brought back to land. Materials scientist Harald van der Mijle Meijer, a TU Delft alumnus and wind energy senior consultant at TNO in Petten, estimates that this amounts to about 1,200 tonnes. He and his group are working on a technique to process plastic composite material, more on this below. The Amalia offshore wind farm had a capacity of 120 megawatts.

By comparison, offshore wind farms built now have capacities of thousands of megawatts. When the turbines from those farms reach the end of their life cycle in 2050, the Netherlands can expect a waste stream of 40,000 to 50,000 tonnes per year. That is 20 to 25 times more than today, states TNO in its Offshore wind farm decommissioning (2021) report, in which Dr Jelle Joustra of TU Delft was involved. He specialises in circular product design with composite materials at the Faculty of Industrial Design Engineering.

The use of composites is rapidly increasing

Harald van der Mijle Meijer and Mariusz Cieplik are developing at TNO a method to evaporate the resin and recover the fibres.

© Jos Wassink

Jelle Joustra investigates reuse of material from wind turbine blades. For example as a picnic table.

© Thijs van Reeuwijk

Incinerate

Joustra can get angry about incinerating composite materials. Yet that is what is usually now done with discarded blades: incinerating them as a raw material for cement. In a position paper, a consortium of seven organisations calls this cement co-processing ‘a sustainable solution for recycling composite materials’. The shredded composite material used to come from recreational boats but now comes increasingly from wind turbine blades. How desirable is this? Joustra taps his hand on the top of the picnic table.

‘Beautiful material that can last for a long time’

The panels for the table have been cut from a wind turbine blade. It feels clean, sleek and solid. “This is beautiful material that can last for a long time. If you can make something like this with it, it’s surely a waste to incinerate?” Besides, incineration is about the only thing composite material is not good at as half of it is made from glass that “doesn’t burn at all.” Pretty inefficient then if discarded wind turbines disappear into the incinerator. But alternatives are under development.

Playground Wikado in Rotterdam.

© Allard van der Hoek

Beams and panels

TU Delft researcher Jelle Joustra looks beyond the creative reuse of whole or partial sheets. Sure, there are original applications, he agrees, but these are incidental. It takes a lot of design effort to give one or two blades a new use, he says. “Such repurposing is difficult to scale. You can’t roll it out at a big scale.” And that is what Joustra, as a researcher in the Design for Sustainability department (Faculty of Industrial Design Engineering), is looking to do. Can you cut a blade into standardised elements? This is what Joustra is working on. Composite material can be cut well with a waterjet. Other types of saws get blunt quickly because of the amount of glass in the composite. Besides this, sawdust from glass or carbon fibre poses risks of lung damage. Turbine blades can be cut into a range of beams and panels. Joustra believes that this opens a world of applications. “It’s high-end material. It stays very stiff and strong, even after 25 years of use.”